Money makes the world go round - the hyperinflation of 1923

- Marleen Tigersee

- Jul 9, 2023

- 4 min read

Ladies and Gentlemen,

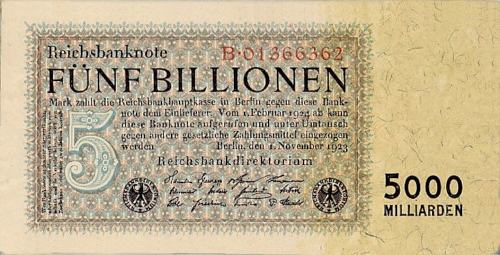

do you sometimes walk through the rows of shelves at your local grocery store and think to yourself: "Wasn't this cheaper before"? And it must not have been so long ago that the increased prices for heating and the like caused you a grey hair or two, am I right? Now imagine that prices were not rising every year, but every day, and that they were rising immeasurably. Millions, even billions, for the simplest basic food items! A frightening thought. Come with me on a journey back in time to the year of the hyperinflation, but be careful not to get dizzy from all the zeros!

1923 is not an easy year for Germany. The population suffers from the high reparations payments resulting from the Treaty of Versailles. The occupation of the banks of the Rhine by French and English soldiers worsens the situation, strikes and political riots are not long in coming. To relieve the financial pressure somewhat, the Reichsbank prints more money, but due to the bad economic situation there are not enough goods to buy for it, which has disastrous consequences: The few goods become more and more expensive and the huge amounts of money in circulation become worth less and less. Many companies are forced to lay off employees en masse. Those who still have work have to hope that they will be paid their wages per week, or better, per day; at the end of the month, they can no longer get anything for it.

As is so often the case, it is the little people who are hit hardest. Assets that have been painstakingly saved for decades are swallowed up by inflation in no time. But not only assets are swallowed up, those who had debts are now also rid of them. Companies that were on the verge of insolvency can take out loans again. By the time the instalments are due, the value of the mark has fallen further and the amounts to be paid are hardly worth mentioning. The losers remain the banks. Stock market speculators also know how to exploit the fall of the mark. Those who can, trade in other currencies, such as the stable dollar or the Swiss franc. As one can imagine, the inflation profiteers do not enjoy particular popularity among the rest of the population. Klaus Mann describes the situation in 1923 as follows:

The bloody turmoil of war is over: let's enjoy the carnival of inflation. It's a lot of fun and paper, printed paper, weak stuff - do they still call it money? You can get a dollar for five billion of it. What a joke! But the Yankees come as peaceful tourists this time. They buy a Rembrandt for a sandwich and our souls for a glass of whisky. Krupp* and Stinnes* get rid of their debts, we of our savings. The profiteers dance in the palace hotels.

Americans like the young Ernest Hemingway, who was working as a European correspondent at the time, could spend nights in luxury hotels for just a few cents and buy up everything that would be unaffordable elsewhere. A fact that contributes to the general displeasure of the Germans. While Hemingway still has to pay 38,000 marks for a bottle of sparkling wine in the summer, the mark continues its rapid decline. The lower the value of the currency sinks, the more banknotes have to be printed again, a vicious circle:

The Germans are swimming in money and threatening to drown in it. A few days ago the Reichsbank put the one-billion-mark note into circulation, now the ten-billion, the hundred-billion, the two-hundred-billion, the five-hundred-billion notes are following. The banks would have to capitulate before the enormous flood of paper if they could not fall back on an army of money counters who stack the notes into towers.**

People with carts full of banknotes, who can hardly get a loaf of bread for it, now characterise everyday life. The need is so great that the price boards at theatres, cinemas or other shops soon indicate food items instead of amounts of money that have to be paid for the respective seats or services.

Franz Kafka, who has just moved to the Grunewald district of Berlin with his partner Dora Diamant, avoids travelling into the city centre so as not to have to witness the images of misery. He writes to his friend Max Brod on 2 October:

I also try to protect myself out here against the real agonies of prices [...] yesterday, for example, I had a strong attack of number madness [...].

Other writers, such as Alfred Döblin, who also lives in Berlin, experience inflation at close quarters. At regular intervals he writes down how the situation is getting worse and worse. In August, grocery shops are already no longer quoting exact prices, but only the number to be multiplied by on the day. In October, he notes:

The situation in Berlin is frightening. [...] The people standing around on the street corners; they now have millions, billions and are trying in vain to buy for it.

But how could this vicious circle be broken? It was to take until December for the politicians to put an end to the number madness, as Kafka calls it. The Rentenmark temporarily becomes the new means of payment, with an exchange rate of 1:1 trillion. This in turn is replaced a year later by the Reichsmark, which finally brings some stability to the ailing Weimar Republic. The payment of reparations is renegotiated with the victorious powers so that the economy can slowly recover.

If I have now piqued your interest in this turbulent year and you would like to know even more about the hyperinflation, the exhibition "Inflation 1923. War, Money, Trauma." is on display at the Historical Museum in Frankfurt until 10 September, I can highly recommend it.

Yours,

Marleen Tigersee

* Alfried Krupp and Hugo Stinnes, major industrialists during the Weimar Republic

** quote from In the frenzy of turmoil - Germany 1923 (original title: Im Rausch des Aufruhrs) by Christian Bommerius, p. 230

Comments